News Releases

News Release

Ulrich Steidl, M.D., Ph.D., Elected to Association of American Physicians

June 10, 2025

News Release

Amanda Raff, M.D. ’98, Appointed Senior Associate Dean for Medical Education

June 5, 2025

In the News

The Future of ART Regimens for HIV Is in Long-Acting Agents

Infectious disease physician, Barry S. Zingman, M.D. shares what to know about recent developments in antiretroviral therapies for HIV.

August 4, 2025

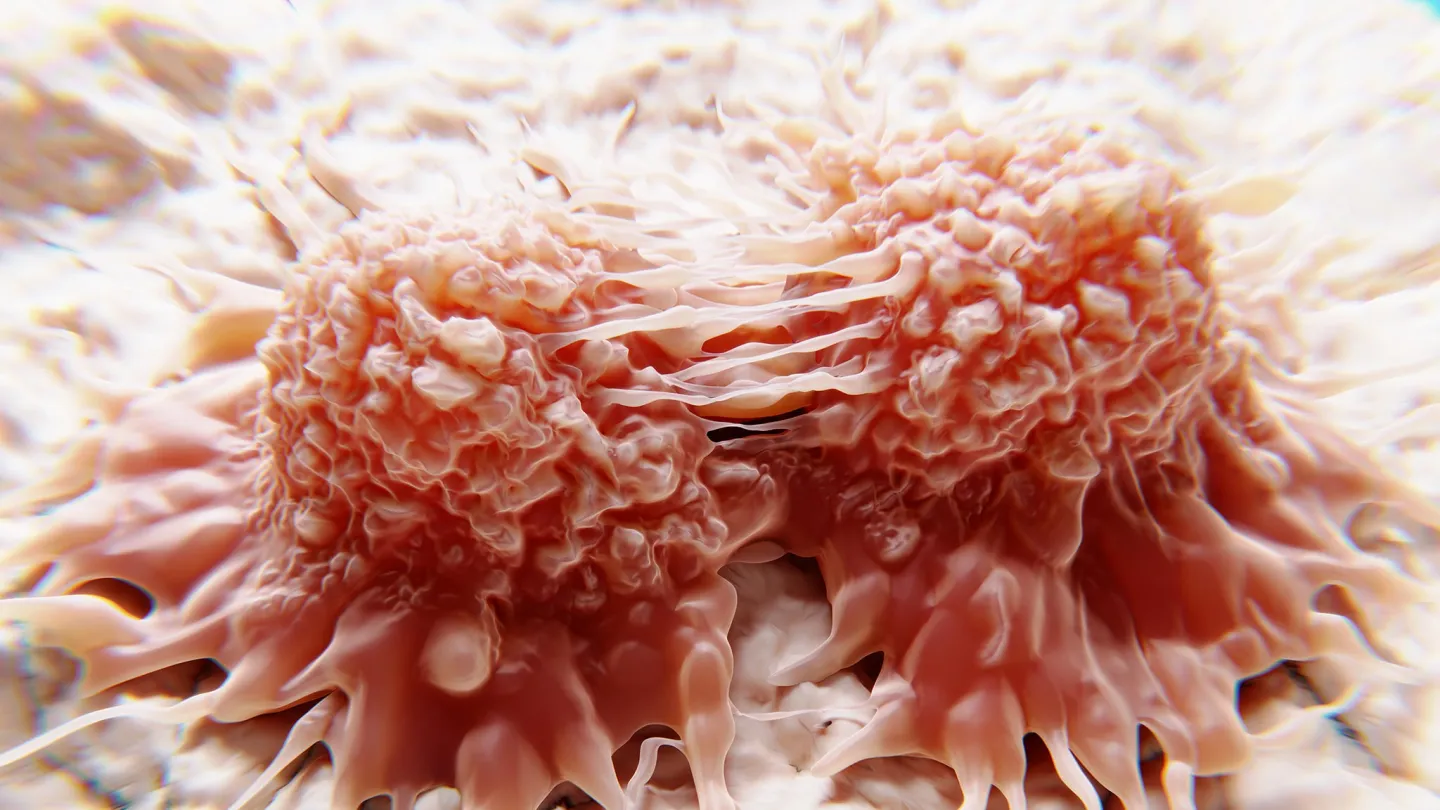

Viral Infections in the Lung Can Reactivate Dormant Cancer Cells

Cancer biologist Julio Aguirre-Ghiso, Ph.D., discusses his Nature study on respiratory viruses and metastasis.

July 30, 2025

Red Light Therapy Can Benefit the Skin, a Westchester Expert Explains

Cosmetic dermatologist, Kseniya Kobets, M.D., shares the benefits of red light therapy for a person’s hair and skin.

July 9, 2025

Header

Experts for Media

Header

Experts for Media

Research

August 6, 2025

July 31, 2025

July 24, 2025