Conducting Research in the Czech Republic

Science and Life in the Czech Republic: An Outsider's Inside Perspective

In the fall of 2013, Einstein fifth-year graduate student Danielle Pasquel spent three months in the Czech Republic working on her thesis research. Her work in the laboratory of Dr. Zdeněk Dvořák stemmed from collaboration between her faculty advisor, Dr. Sridhar Mani, and Dr. Dvořák. Here, in her own words, Ms. Pasquel reflects on the value of her studies abroad.

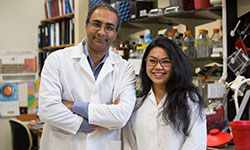

Ms. Pasquel with her faculty advisor Dr. Sridhar ManiEach year, scientists of all levels—professors, postdocs and students—travel the world presenting their work and attending conferences. Last fall, I had the unique opportunity to live abroad for three months while conducting my thesis research in a collaborator’s laboratory.

Living and working in the Czech Republic has been a highlight of my graduate education. I learned many invaluable skills and life lessons. The experience was particularly rewarding since “studying abroad” for an extended period isn’t often possible. My exchange experience was arranged somewhat informally, arising from a mutual investment in collaboration and the friendships formed from it, rather than through a special program or fellowship.

Collaboration Leads to Connections

In the historic town of Olomouc, located in the Moravian region of the Czech Republic, I worked in the laboratory of Dr. Zdeněk Dvořák, head and professor of cell biology and genetics at Palacky University. Dr. Dvořák collaborates on research with my Einstein advisor, Dr. Sridhar Mani, in relation to their shared research interests in orphan nuclear receptors and drug metabolism.

Ms. Pasquel with members of the Dvořák lab, at Palacky University The idea for me to work in Dr. Dvořák’s lab occurred after he sent his then-Ph.D. student Aneta Vávrová to work in our lab at Einstein during the fall of 2012. As we made plans for Aneta’s visit, Dr. Mani connected me with her so that we could begin developing a joint project.

In the six months leading up to Aneta’s arrival, she and I got to know each other through e-mail correspondence. It was then that we discovered that our thesis projects were uncannily similar—we were both investigating the causes and consequences of post-translational modification (PTM) of pregnane X receptor function. We also found that many of our experimental approaches were the same. The main theoretical distinction between our projects was the class of PTM on which we would each focus.

Discovering the broad overlap of our research excited us because we knew that our respective ideas and technical skills would complement each other well. In our three months of working together at Einstein, Aneta and I made some progress on the project. But much work remained. Dr. Mani suggested that I visit Aneta’s home lab the following year.

Conquering Culture Shock

In Dr. Dvořák’s lab, getting acclimated proved a challenge. Aside from running experiments, simply getting familiar with the topography and the practices of a new lab introduced unexpected obstacles—from learning where they kept common supplies and reagents and how to operate new instruments, to remembering the names of my many new Czech colleagues (with often difficult-to-pronounce Czech names). Also, even though everyone spoke some level of English, many things in the lab were written in Czech, including labels on reagent tubes and bottles, signs posted throughout the lab, and even PowerPoint presentations during lab meetings.

Although I was already quite experienced with many of the standard experimental techniques used in the Dvořák lab, I realized that they did things a little bit differently than I was accustomed to, including the protocols they used for familiar assays and the way they prepared and stored common reagents. This forced me to critically understand why things were done a certain way instead of just blindly following a protocol, evaluating both its underlying biological rationale and the practical rationale. At the same time, learning these alternative ways to achieve the same goal taught me how to be more flexible and resourceful when planning and conducting my experiments.

Invaluable Take-Home Lessons

Olomouc, Czech Republic, where Ms. Pasquel spent three months working with her collaborator, Dr. Zdeněk DvořákAs researchers, when we learn to do something in a way that works, we tend to avoid deviating in fear that it may no longer work. While this practice is conducive to consistency and reproducibility—important principles of scientific research—I realized that it’s also important to leave room for creativity, even when trial may lead to error. I find that this lesson proves useful with regard to experimental methodology and to life in general.

My educational experience in the lab was further enhanced by my living experience—adapting to a new country, new people and a new culture. In the beginning, I often felt lost and confused as I learned how to navigate the streets, use the public transportation system and communicate with the local residents. As a foreigner, I felt alienated at first, but quickly began to embrace my circumstances. I was forced to confront unique challenges and live outside of my comfort zone.

Even ordinary tasks such as grocery shopping, ordering food at a restaurant and purchasing train tickets could be stressful because of my unfamiliarity with everyday etiquette and the Czech language. As I became familiar with the town and more confident using the few Czech phrases I knew, I began to take journeys on my own.

The Czech Republic is a wonderful country comprised of a few large metropolitan cities, many small countryside villages and diverse natural landscapes. In using some of my weekends to tour different regions of the country, I learned about its rich history and cultural traditions. I often took the three-hour train ride from Olomouc to Prague, the nation’s largest city and its capital. I also visited several of the charming villages peppered throughout the Czech countryside, including the humble hometown village of my Czech friend Michaela, called Dymokury. And my lab colleagues took me for a weekend to South Moravia, to tour the vineyards and hike the hills of the Palava UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. I had an uncut sampling of what the real Czech Republic has to offer.

Cutting the World Down to Size

Scientists and other professionals know well that information exchange and collaboration should not be confined to the walls of a lab or geopolitical borders. Working abroad underscores how encountering different ways of life and new challenges encourages one to be more adaptable. I had to open my mind to new ideas and attitudes, adopt new customs and behaviors and even contemplate my own cultural truths. In the process, I learned that international travel experience and “cultural competency” are important and personally valuable attributes, especially in this increasingly globalized world.

Upon reflecting on my entire three months abroad, I feel mostly gratitude—for the rare opportunity to work and live in the Czech Republic, for the invaluable scientific knowledge and skills I gained working with Aneta in Dr. Dvořák’s lab and for the new friendships I formed inside and outside of the lab.

I returned to the Bronx with a new appreciation for Einstein and my home lab as well. I was glad to re-enter the Einstein community, working at my old lab bench surrounded by my lab mates. I am grateful to Dr. Mani for his support and encouragement, to Dr. Dvořák for welcoming me in his lab, to Aneta for her contribution to the project and helping me with experiments and to the Czech Republic for providing such rich cultural and educational experiences both in and out of the lab.

Posted on: Thursday, June 26, 2014