Leaving a Legacy

A 55-Year Legacy of Wisdom, Excellence, and Thoughtfulness

Fifty-five years ago, Einstein opened its doors, extending New York City’s medical excellence to the Bronx. Among the junior faculty recruited to the newly established medical school was Dr. Milford Fulop, who went on to spend his professional life as an internist at Jacobi Medical Center while also holding a number of administrative positions in the department of medicine — including chief of medicine at Jacobi, interim chair of the department and, most recently, vice chair for academic affairs. On March 31, 2010, after 55 years on the Einstein faculty, Dr. Fulop retired.

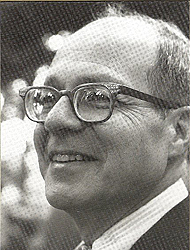

Dr. Milford Fulop, now —

shortly before his retirement on

March 31, 2010At a symposium held in Dr. Fulop’s honor on April 14, Dr. Irving London, who served as founding chair of medicine at Einstein, noted, “From the very start Milford set standards of excellence for the department, and for 55 years he has been a remarkable center for these values.”

“I have deeply appreciated Milford’s wise counsel,” said Einstein’s current chair of medicine, Dr. Victor Schuster. “He has put the wind in our sails as a department with all of the history and legacy behind us, and and it's been a real pleasure to work with him and know him.”

Milford Fulop was born in the Bronx in 1927, the oldest of three children to Ettu Karl and Herman Fulop, two young immigrants from Hungary. He was just eight years old when his father died of rheumatic heart disease. He and his siblings were raised by their mother.

During the 1930s, Dr. Fulop fulfilled a childhood marked by academic excellence, entering the newly opened Bronx High School of Science at age 11. He was awarded a Pulitzer scholarship (full tuition, plus support) for Columbia College at age 15. After two years as an undergraduate, he was admitted to Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and Alpha Omega Alpha.

He credits his success in part to his mother, who came from a large family of high school and college graduates, including two lawyers and two engineers. “There was never any pushing, but she often talked of her brothers and I think she felt I at least ought to emulate them,” he said.

After graduating from medical school, Dr. Fulop completed an internal medicine residency at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. He served for two years in the U.S. Air Force as a medical officer during the Korean War, stationed in upstate New York and at a forward fighter plane base in Kimpo, Korea. When the College of Medicine recruited its first class and began instruction in 1955, Dr. London recruited Dr. Fulop to develop the medicine residency program at Bronx Municipal Hospital Center (later renamed Jacobi Medical Center).

“We had an unknown house staff, a load of patients ready to occupy medical wards at Jacobi, and a yet-to-be-developed chest service that would become the largest in New York City,” recalled Dr. London. “There was a resident at Columbia-Presbyterian who was universally recognized as the best and brightest, and when he accepted the opportunity to embark on a career at a medical school yet to prove its mettle, on a service that would be full of problems, I knew that we were very lucky.”

Of that time, Dr. Fulop noted, “The College of Medicine started from ideas germinating in a number of minds, a little house on Morris Park Avenue, and a deal made with the city. The faculty was small enough that we each knew one another on a first-name basis, and the exchange of ideas and conversation was perfectly free.”

In his role, Dr. Fulop oversaw residents and orchestrated a number of medical school courses, including Physical Diagnosis, Laboratory Methods, and third- and fourth-year clerkships.

“In 1958, this young fellow just a few years older than I was seemed to know everything that was going on, and he even seemed to know what we were thinking about,” recalled, Dr. Leslie Bernstein, professor emeritus of medicine. “He’s just as amazing now as he was in 1958.”

“Making rounds with Milford was memorable. I think he was the first person who used thoughtfulness as a way of developing clinical skills,” said Dr. Harold Adel, professor emeritus and one of Dr. Fulop’s first trainees, who later assisted him in leading the residency at Jacobi.

In 1970, after Dr. London left Einstein to develop and head the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology, Dr. Fulop became Einstein’s acting chair of medicine; it was a position he filled for the next five years. Additionally, he served as vice chair and director of medicine at Jacobi until 1993, and he continued to make teaching rounds with students and residents at Jacobi.

“Generations of patients and trainees were fortunate to have a doctor when Milford made ward rounds,” noted Dr. David Hamerman, distinguished university professor emeritus and chair of medicine at Montefiore Medical Center from 1968 to 1979.

“Fostering the careers of the students and residents who came through our training programs has given me the greatest happiness,” acknowledged Dr. Fulop.

As he advanced through the academic ranks, Dr. Fulop was promoted to professor and held the Gertrude and David Feinson Endowed Chair in Medicine in 1968; he became distinguished university professor in 1994. Among his numerous accolades, Dr. Fulop received the College of Medicine's Honorary Alumnus Award marking the silver anniversary of Einstein's first graduating class in 1984, was named a Master of the American College of Physicians in 1993, and was honored with Einstein’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Clinical Teaching in 2000.

Dr. Milford Fulop, then —

early in his career at Einstein“Milford’s influence has been infinite. Einstein has probably the largest number of medical students going into internal medicine and I think that’s been largely due to him,” said Dr. Edward Burns, executive dean and an Einstein alumnus who is a member of the medicine department (hematology).

Dr. Fulop’s influence on Einstein was not limited to clinical and educational endeavors. His research included whole-animal studies focusing on the renal excretion of bilirubin and of phosphate (with Dr. Paul Brazeau, former chair of pharmacology at Einstein). He also undertook observational studies of acid-base disturbances in patients, particularly those with pulmonary edema (with Dr. Arnold Aberman) and with alcoholic and diabetic ketoacidosis (with Dr. Henry Hoberman, professor of biochemistry and a fellow founding faculty member of Einstein).

“The time I spent in Milford’s renal clearance laboratory converted me from a young man with a general, casual way of thinking about science to one with a much more rigorous, reproducible, infinitely concerned-with-detail approach to science. I took from this the enormous benefit of having a quintessential mentor, a person who made an indelible imprint on my life at a very important stage of my career,” recalled Dr. Barry Brenner, who went on to lead the renal division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

On a more personal note, Dr. Fulop married Dr. Christine Lawrence, a fellow Columbia graduate. In 1957, Dr. Lawrence became director of hematology at Jacobi and professor of medicine (and later, distinguished university professor emerita) at Einstein. Their son Michael is a psychiatrist in Baltimore, and their daughter Tamara (class of 1993) is director of breast imaging at Beth Israel Medical Center. They have four grandchildren.

Of his long career he said, “I think some of the major challenges have been related to helping my wife raise our children. While she played a much stronger role than I did, she herself had a very busy academic and clinical career as a hematologist, and we had a busy time of it. Among my great joys, as an outgrowth of that, have been the children. They are terrific and have been very successful professionally.”

Today, as people with HIV can expect to live near-normal lives and continuing medical education can be conducted through an iPod, Dr. Fulop has written his last scientific paper and attended his final early-morning administrative meeting. Still, he plans to continue participating in teaching conferences and making rounds with the chief residents at Jacobi.

“I have enjoyed my career in medicine, particularly taking care of patients and the opportunity to interact with the many residents who taught me a great deal,” he said. "I’ve had a very, very happy career.”

Posted on: Tuesday, May 25, 2010