The Domestic Gain from Global Health Training

The beautiful Kisoro countryside is marked by sharp hills, towering volcanoes, and serpentine lakes accessible only by walking hours along dirt roads. For the underserved African region of Kisoro, Uganda, a steady infusion of young, energetic physicians can drastically improve villagers’ access to quality medical care. But when these physicians return to America, they bring home the benefits of stronger examination skills; improved bedside teaching; and a more evidence-based, cost-effective work style.

For eleven months of each year, Einstein faculty and residents and medical students join with Doctors for Global Health and Montefiore Medical Center to help staff Kisoro District Hospital (KDH), located in a largely rural area of southwestern Uganda, a few miles north of Rwanda and east of the Congo. When Dr. Gerald Paccione, Professor of Clinical Medicine and Director of Global Education for the Primary Care and Social Internal Medicine Residency Program, first visited the district of Kisoro in 2005, he found that the needs of the villagers were stark (families typically subsist on less than two dollars a day and women have an average of eight children), but the community was warm, welcoming and eager to facilitate a sustainable partnership with Einstein.

The village of Kisoro has one doctor for every 40,000 people, and KDH can only employ about half the staff it is funded for to serve its high-needs population of 150-200 patients each day. Basic necessities such as sheets and mattresses are precious at this hospital, and there are few diagnostic tools beyond a centrifuge and microscope, as well as an X-ray and an ultrasound that are often out of service.

Reclaiming the “Lost Art”

The Medicine wards of Kisoro District HospitalRather than lamenting what KDH lacked, however, Dr. Paccione saw what it could offer: extensive opportunity for residents and junior faculty to learn how to conduct thorough physical exams and use critical thinking in place of tests. “To successfully treat patients in a place without resources, you have to be the instrument of the diagnosis,” he said. “Uganda is our laboratory—it provides meaning for the rhetoric of teaching clinical skills, and teaches us to practice effective medicine outside the hospital setting.”

"When there's no chest X-ray or CT scan to double check your exam, you listen longer, percuss with better technique, and palpate deeper. You think harder because with less information, there are fewer pieces of the puzzle," said Dr. Samuel Cohen, a resident who arrived back from Uganda in late November 2012.

Residents and senior medical students prepare for the Uganda experience through the prerequisite Global Health Elective, which packs 150 hours of teaching time into four weeks and provides an intense introduction to Global Health from both the public health and clinical perspectives. The course, and Uganda experience, recently received New York State accreditation for 12-credit Advanced Certificates in Global Medicine for residents.

About twenty residents and sixteen medical students travel to Kisoro over the course of the year, serving one-month rotations on the KDH medical wards and running the twice-weekly Chronic Care Clinic. Supervision is provided by a faculty member from the Global Health and Clinical Skills Faculty Development Fellowship (GHACS). Faculty demonstrate cost-effective clinical skills refined through their own KDH experience. Near-daily email exchanges with Dr. Paccione provide extensive discussion and coaching to augment the diagnoses of diseases such as advanced-stage malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, pneumonia, valvular and restrictive heart disease, diarrhea, and typhoid. Residents who are rounding in the Bronx gain from the Uganda experience as well, discussing case studies of patients seen at KDH during GHACS-sponsored weekly teaching rounds and gathering relevant literature for their peers.

A patient is transported into KDH. "This long-distance exchange facilitates both residents' learning here and their practice over there," said Dr. Paccione. "While many residency programs are bemoaning the fact that their residents are only learning medicine by computer, our residents are learning how to interpret a patient’s history, how to listen and make biological sense of what a patient is telling them, and how to perfect their skills in the physical exam."

"In my clinical work, I choose to continually develop my clinical reasoning and physical diagnosis skills in order to make management decisions that minimize unnecessary testing," said Dr. Sheira Schlair, who helped establish the program in 2007. "This is truly a life's work, and for me, these lessons were first learned in Kisoro."

The Payback

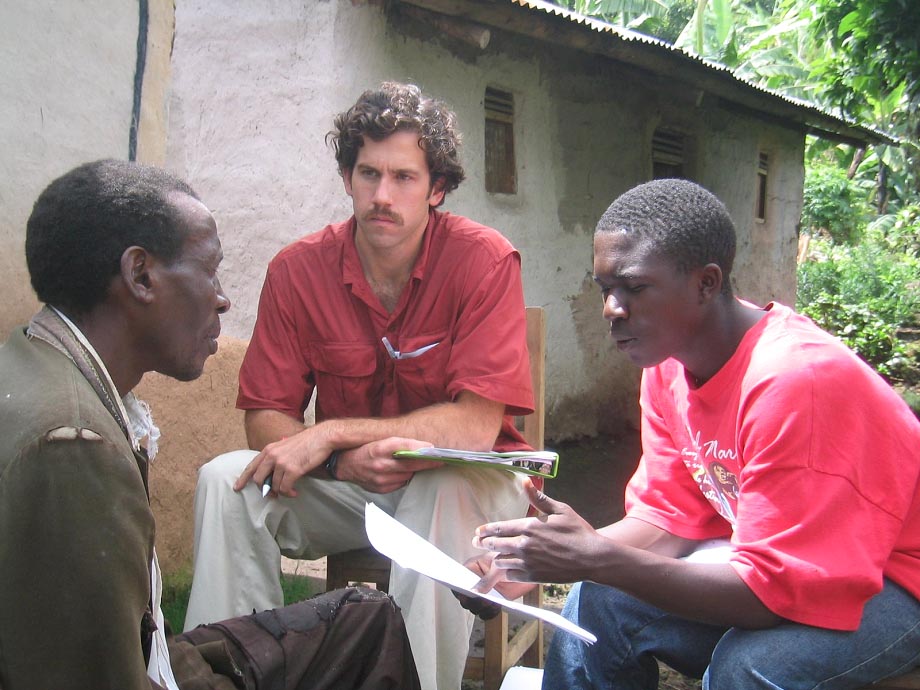

Kisoro residents.According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, our nation’s annual healthcare spending now surpasses $2.6 trillion. Physicians who receive global health training, however, may be able to help better control healthcare costs.

Without a CT scan machine at KDH or at the Chronic Care Clinic, residents routinely practice basic skills that many of their peers lack: the ability to hear a heart murmur, feel a spleen, hold an ophthalmoscope, or describe a rash or a node. “Residents in our program gain the skills necessary to make confident diagnoses, restrain the excessive use of tests, and operate comfortably and productively in a medical office,” said Dr. Paccione.

"By the end of the month I could quickly diagnose heart failure and its likely etiology," said Dr. Christopher Knudson, a third-year resident. "I've told every intern considering cardiology that they must go to Kisoro, as it will likely be the richest training of their career."

“The emphasis on history and physical examination and the ability to refine those skills with Jerry was absolutely the most defining aspect of the experience,” said Dr. Rohit Das, now chief resident of the Internal Medicine Training Program. “Such skills are overlooked in Western medicine, where easily available imaging studies have, to a certain extent, compromised the necessity to learn them.”

A hospital without reliable diagnostic equipment, however, is hardly a utopia when it comes to patients' needs. "There are certainly times when I wish I had access to modern medicine," said Dr. Erin Goss, a faculty fellow currently in Kisoro. "An 18-month-old child came in with difficulty breathing, and needed oxygen and nebulized epinephrine, but the power was out. I did my best with giving her epinephrine IM, and steroids and antibiotics, and she improved, but I still had to transfer her to another hospital that had power. It's painful to not be able to give life-saving therapies to someone so young."

Those Who Teach

A teaching session.Internal Medicine physician-educators with strong clinical skills may provide a solution to the rising need for healthcare cost containment. However, finding the right people for these roles requires the creation of attractive, career-building job options targeted to physicians willing to work for less in the interest of their ideals.

A particularly innovative aspect of the Uganda program is its two-year GHACS fellowship, established in July 2012. Through this uniquely designed fellowship, four junior faculty members spend three months apiece in Kisoro and eight months at Montefiore each year. In Kisoro, faculty-fellows supervise residents, see patients, and sponsor research projects in medical education, clinical assessment and diagnosis, and community medicine (previous research has resulted in extensive programming to address issues such as malnutrition, literacy, and maternal mortality). At Montefiore, they cover evenings and weekends at the Comprehensive Health Care Center (CHCC), supervise residents in researching and discussing patient cases sent from Kisoro, teach clinical reasoning and physical diagnosis, and complete their Kisoro-based research projects. Faculty fellows are funded at 60-70% of their U.S. equivalent salary, and emerge with strong hands-on clinical skills, positioning them as outstanding medical educators.

The next generation.“Our faculty-fellows gain mentored experience in medical education, clinical skills and global health; Montefiore meets its ACGME requirements for supervision abroad and gets low-cost, enthusiastic medical educators who are experts in clinical skills and reasoning; and the Kisoro medical system benefits from dedicated, experienced clinical supervisors,” said Dr. Paccione. “It’s a true win-win-win.”

The strengthened supervision provided by faculty fellows improves the efficiency at KDH. "The residents I've worked with in Uganda were incredibly motivated to learn and to do their best to care for their patients," said Dr. Goss. "I can help them to work effectively within a foreign system within a much shorter period, so they can focus on unraveling the mysteries of the patient in front of them."

"Even one month on the wards in Kisoro opened my eyes to the sights and sounds we commonly miss and now, having been back twice more, I feel much more confident in my ability to teach what I see and diagnose conditions without expensive medical tools," said Dr. Shwetha Iyer, a faculty fellow who recently returned from a third trip to Kisoro.

A New Attitude

On many levels, physicians' time in Uganda is transformative.

"The Uganda experience rejuvenated me and reminded me of why I'd initially decided to become a physician," said Dr. Cohen. "I've returned to the United States with a renewed interest in how we as physicians decide which tests to order. There's so much diagnostic testing which has become the standard of care in Western medicine without rigorous review."

"Working in Kisoro gave me so much more confidence," said Dr. Knudson. "I trust my own abilities, and I order far less (what I now consider useless) testing, and think more."

"Living the intensity of the day-to-day clinical routine, bearing witness to the profundity of human need, and growing an appreciation for Ugandan human vitality was literally transformative for me," said Dr. Schlair. "I returned home with an inner confidence and clarity about my mission and skills as a future primary care physician that I can still appreciate now, five years later."