Samuel Silverstein, MD '63 has enjoyed a lifetime of exploration, from Antarctica's mountains to innate immunity.

Dr. Silverstein was once named the University of Colorado Medical Center's surgical intern of the year–even though his internship was in medicine.

He was caring for a patient who had developed peritonitis after undergoing surgery for a ruptured appendix. Though on antibiotics and nasogastric drainage, the man was declining. “I remembered that patients on nasogastric drainage sometimes develop paradoxical aciduria due to potassium depletion,” Dr. Silverstein recalls. I treated him with intravenous potassium, and it worked.”

Dr. Silverstein, John C. Dalton Professor Emeritus and past Chairman of the Department of Physiology & Cellular Biophysics at Columbia University, became a cell biologist because “if you don't understand how cells work, you can't understand normal or abnormal human physiology.”

Yet his diagnostic skill, broadly speaking, has led to many subsequent achievements, from discoveries about the immune system to scaling unexplored mountains in Antarctica–now home to the 15,720-foot Silverstein Peak–to helping former Representative John Porter secure an increase in the National Institutes of Health's 1996 budget. At 87, he is seeking to expand his Columbia-based, award-winning professional development program for experienced secondary school science teachers to all seven New York City medical schools.

A Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, Dr. Silverstein enjoys posing answerable questions. “Cause-and-effect thinking is essential,” he says. “Everything has antecedents. You observe something and ask, why does that happen?” Witness Dr. Silverstein's decades-long effort to understand how white blood cells defend us against microbial infections.

As a senior Einstein medical student in the labs of microbiologist Philip Marcus and cell biologist Alex Novikoff, he used electron microscopy to identify the mechanism used by influenza-like viruses to enter mammalian cells. He built on that work in the 1970s, as an associate professor in the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology at Rockefeller University. There he discovered how macrophages--a type of white blood cell that defends humans against microbial pathogens--discriminate between native and antibody-coated bacteria, both of which are in contact with a microphage's outer or plasma membrane. With ingenuity, he showed that macrophages avidly ingest antibody-coated bacteria but ignore bacteria that are not coated with antibodies. These experiments identified the general principle that white blood cells discriminate between microbes bound for ingestion and killing versus microbes that escape recognition, by sensing interactions between the receptors that the white blood cells express on their plasma membranes and ligands for these receptors, such as antibodies, on the surfaces of microbes. Dr. Silverstein termed this process “zippering,” earning him the nickname “Dr. Zipperstein.”

In the late 1990s, Dr. Silverstein, his students, and his colleagues focused on killing of antibody-coated bacteria in tissue-like environments by neutrophils, the most abundant type of white blood cell in human blood and inflamed tissues. They discovered that a critical concentration of neutrophils is required to reduce the concentration of antibody-coated bacteria, even if there are only a small number of bacteria present. This “critical concentration” rule can be used to benchmark whether a person with a low blood neutrophil concentration--due to an adverse drug reaction, cancer chemotherapy, or other conditions--is in danger of a potentially lethal bacterial infection. In further studies, Dr. Silverstein, his students, and his colleagues extended these observations to cancer immunotherapy, demonstrating that a critical concentration of cytolytically active, tumor antigen-specific T-cells is required to eliminate tumors.

Base Camp

Mountaineering– “a thinking person's sport”–has also profoundly shaped Dr. Silverstein's thinking. “Medicine appeals to my sense of humanity, but research appeals to my sense of adventure. And in my life, adventure has always won out.”

When Dr. Silverstein was a high school student at Fountain Valley School in Colorado, a teacher, Robert Ormes, author of the first climbers guide to the Colorado mountains, engaged students in technical rock and ice climbing, guided them to the summits of Colorado's 14,000-foot peaks, and invited them to American Alpine Club section meetings to hear lectures by leading American mountaineers. On one such occasion, Dr. Silverstein was in the audience when members of the 1953 American Alpine Club--sponsored K2 expedition described their unsuccessful and near fatal attempt to climb that mountain. Their lecture had a life-long effect on Dr. Silverstein. “I decided I wanted to climb something that had never been climbed,” he recalls.

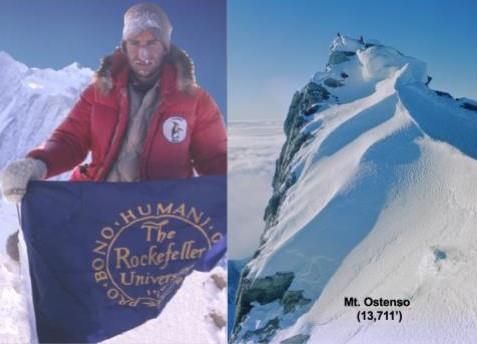

Samuel Silverstein, MD, then a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the Laboratory of Cell Biology at Rockefeller University, on the summit of Mt. Ostenso, Sentinel Range, Antarctica, holding the Rockefeller University's flag.

Samuel Silverstein, MD, then a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the Laboratory of Cell Biology at Rockefeller University, on the summit of Mt. Ostenso, Sentinel Range, Antarctica, holding the Rockefeller University's flag.

At Dartmouth Dr. Silverstein joined the mountaineering club. In the summer of 1959, immediately before his first year at Einstein, he organized two expeditions to British Columbia's unmapped and unexplored Battle Range. He and his companions made the first ascents of the range's principal peaks and named and surveyed them. During his first year as an Einstein medical student, Silverstein completed an article describing these expeditions, along with a map of the range he created with the assistance of members of Einstein's Medical Illustration Department and published them in the 1960 Canadian Alpine Journal. In 1962, Einstein Assistant Dean Joseph Hirsch gave him permission to skip a required public health rotation, thereby enabling him to join his friends in making the first ascent of Denali's Southeast Spur.

During the austral summer of 1966-67, Dr. Silverstein, together with a former Fountain Valley classmate, and eight other leading American expeditionary mountaineers, participated as co-organizer, expedition physician, and climber in the National Geographic-National Science Foundation-American Alpine Club-sponsored American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition, which explored and made the first ascents of Antarctica's four highest peaks, Mts. Vinson (16,050'), Tyree (15,919'), Shinn (15,292'), Gardner (15,030'), and two others, Mts. Ostenso (13,711'), and Long Gables (13,620'). On their return, the National Geographic Society honored all members of the team in a Washington D.C. Constitution Hall ceremony, led by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. Fifty years later, all members of the team were again honored in Washington D.C., this time with the American Alpine Club President's Gold Medal. Damien Gildea, author of the definitive book, Mountaineering in Antarctica, characterized the expedition as “an incredible achievement,” and “one of the most successful mountaineering expeditions of all time.”

Field Guide

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Silverstein summoned his self-proclaimed “chutzpah” to forestall planned cuts to the NIH budget. NIH was already “starving,” he says, “funding fewer than 25% of investigator-initiated grant applications.” Dr. Silverstein, then-president of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, met with Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, accompanied by top pharmaceutical and biotech executives whose companies made significant contributions to both Democrats and Republicans and employed very large numbers of people. Speaker Gingrich was so impressed by the group's arguments for increased NIH funding that he reversed his previous recommendation for a 5 percent cut in its budget. In the end, NIH got a 7 percent increase. For Dr. Silverstein, the meeting is a symbol of a bygone political era. “My experience in Congress taught me two important lessons: first, don't assume that elected officials are knowledgeable about the topic you have met with them to discuss. Second, that they'll dismiss your arguments on political grounds alone. The key to success is articulating a well-thought-out, evidence-based position concisely, logically, and with evident conviction.”

Legacies

That has been Dr. Silverstein's modus operandi in expanding his Summer Research Program for Science Teachers, which he established in 1990. Participating teachers spend two summers in Columbia's labs, assisting scientists in their work. He hatched the program after giving a lecture for high school science students and their science teachers in which he used ping pong balls, colored differently depending on the amount of lead he had loaded into them, to illustrate how different cellular organelles can be separated from one another by sedimentation in a centrifuge so they can be analyzed chemically and physiologically. “Afterward, teachers approached me as though I was doing magic. They weren't familiar with then contemporary methods in cell biology. Science is fast-moving–you must teach kids both the facts and how we determine them.”

Equally important, “most teachers' academic success plateaus after their fourth year of teaching. As in every profession, they need to keep up with advances in their fields, both to keep themselves motivated and to demonstrate to their students that science is a dynamic and ever-advancing discipline.”

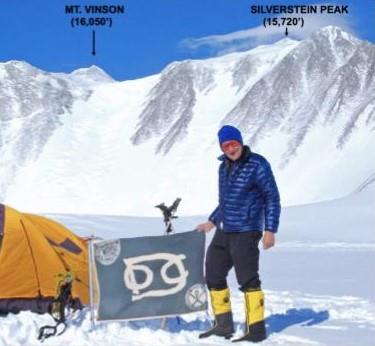

Samuel Silverstein, MD, holding a Dartmouth College Outing Club flag at Mt. Vinson Base Camp on the Branscomb Glacier on his return to Antartica in 2006, at the invitation of Antarctic Logistics and Expeditions LLC, for a 40th Anniversary ascent of Mt. Vinson (center arrow), Antarctica's highest summit.

Samuel Silverstein, MD, holding a Dartmouth College Outing Club flag at Mt. Vinson Base Camp on the Branscomb Glacier on his return to Antartica in 2006, at the invitation of Antarctic Logistics and Expeditions LLC, for a 40th Anniversary ascent of Mt. Vinson (center arrow), Antarctica's highest summit.

In his 2009 Science magazine article about the program, Silverstein reported that students taught by graduates of his Summer Research Program exhibited increased interest and improved academic achievement in science compared to students of non-participating teachers. The program has already been replicated by Questar III BOCES, a New York State Education Department school support agency, as well as Cornell University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He is now working to expand it to all seven New York City medical schools.

“Medical school faculty do basic and applied research using all modalities of contemporary science, mathematics, biology, chemistry and physics,” he says. “If you can take college students into your lab, you can take high school science teachers.”

Dr. Silverstein's achievements in science, education, and public policy have been as widely recognized as those of his in mountaineering and geographic exploration. He is an Honorary Alumnus of Albert Einstein College of Medicine; a member of the National Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; a recipient of the Society for Leucocyte Biology's Lifetime Achievement Award, the American Society for Cell Biology's Bruce Alberts Award for Excellence in Science Education, and the New York City Mayor's Award for Public Understanding of Science and Technology; a past member of the Council of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Chairman of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Cell Biology, the Boards of Directors of Research America, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, the Keystone Symposia, and the Arnold Gold Foundation for Humanism in Healthcare.

Dr. Silverstein has left a bequest in his will to help support scholarships for Einstein medical and graduate students. By making this pledge, he became a member of the Albert Einstein Legacy Society and established his own Einstein legacy. “Without Einstein, I wouldn't have had the career I've had,” he says.

Case in point: as a second-year medical student he studied pathology in a course designed by Pathology Department Chairman Alfred Angrist. “One of the course requirements was to participate in an autopsy,” he recalls. “Mine was of an elderly gentleman who had suffered from cancer for nearly four years. His medical record indicated that he had an exceptionally loving and caring family. The day after the autopsy, Dr. Angrist, knowing only the length of the deceased man's illness but nothing of his social history, examined the man's organs and discussed the autopsy findings with me and the other students assigned to this case, At one point Angrist picked up a piece of vertebral bone, felt it, and exclaimed, 'This man must have had a very loving and caring family.'” Silverstein reported saying, “You're right, Dr. Angrist, but how did you know that?” Angrist responded, “Feel the bone's trabeculae. This man is in perfect nitrogen balance. No one with this much disease for this long can remain in perfect nitrogen balance without a loving, caring family.” “Angrist's comment focused my life,” Silverstein says. “I said to myself, 'That's the kind of humanistic physician and insightful medical scientist I want to become'--then and forever after.”