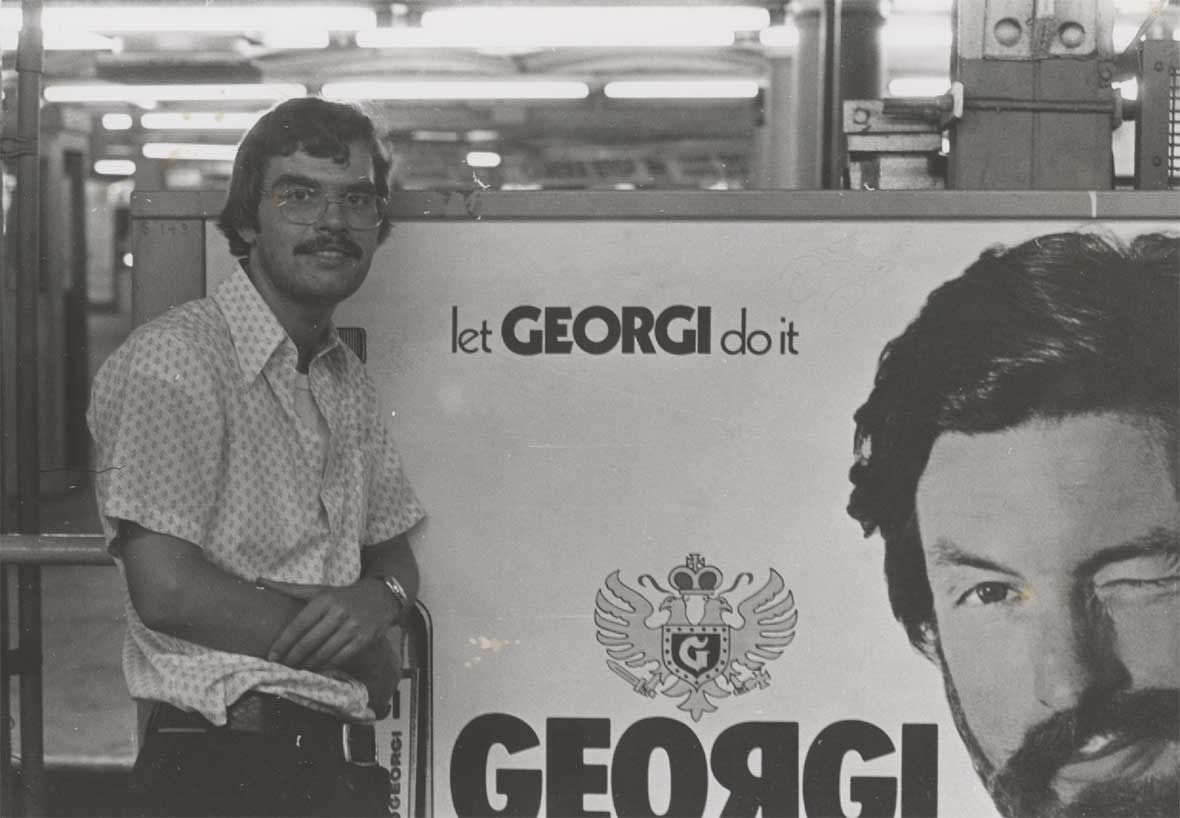

George Fulop, M.D. ’80, NYC subway, 1979

George Fulop, M.D. ’80, NYC subway, 1979

George Fulop’s journey to gratitude began in Hungary in the 1950s. “My parents carried me across the Yugoslav Alps in heavy snow during the Hungarian Revolution,” he says, fully appreciating how hard it must have been. After almost a year as refugees, the family emigrated to the United States; young George grew up in Brooklyn’s impoverished Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood. “I saw the best and the worst that life can throw at you,” he says. He attended Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan and graduated from Columbia University in 1976.

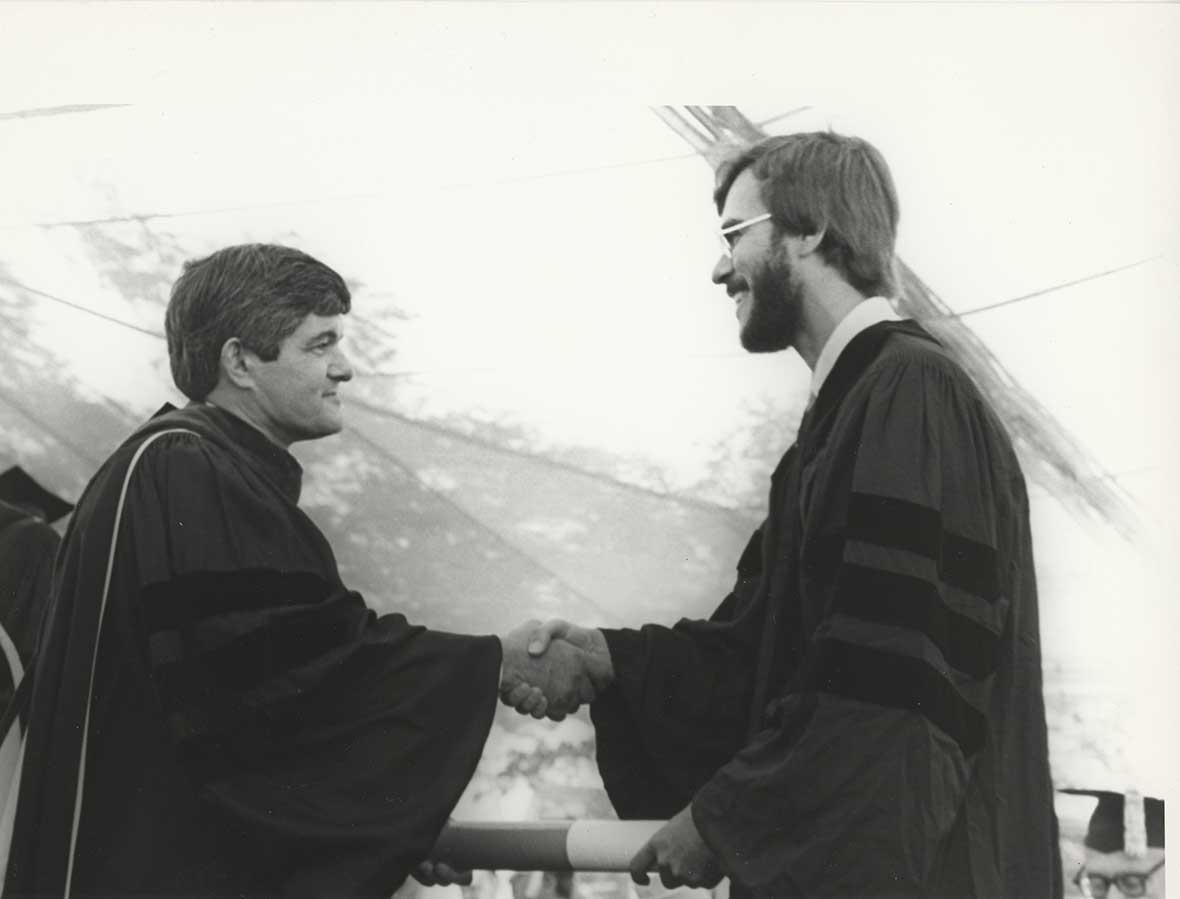

AECOM Graduation, Dean Ephraim Friedman and Dr. Fulop, 1980

AECOM Graduation, Dean Ephraim Friedman and Dr. Fulop, 1980

A Mountain of Debt

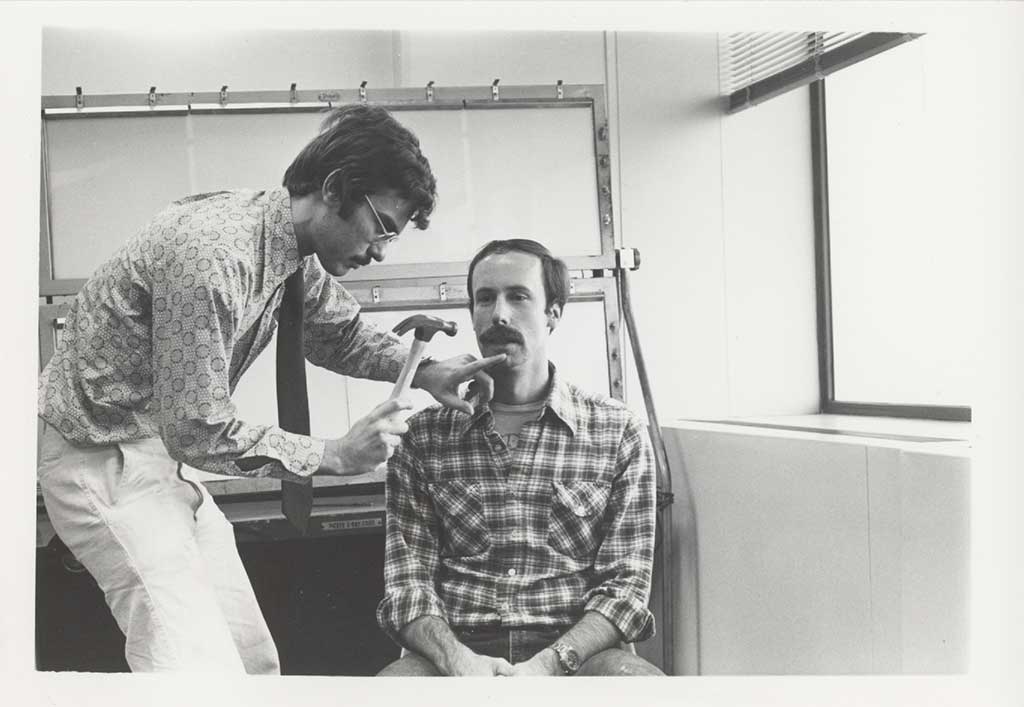

During this time, he encountered a professor who talked about the mind and body interface. Inspired, he sought medical schools strong in behavioral medicine and matriculated at Einstein. There he met James Strain, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, but Dr. Strain did not become a mentor until later: George was working hard to pay down his debts at Columbia and Einstein with outside jobs and had no time to cultivate relationships. “During my second or third year,” he recalls, “Mr. Greenberg calls me into the financial aid office and says, ‘George, you have the highest debt load of any student in Einstein.’ Then he offers me a lower-cost loan! Who could forget such a thing? That special feeling for Einstein became another part of my motivation to say ‘thank you,’” he says.

After graduating in 1980, Dr. Fulop trained in medicine at Montefiore Medical Center and in psychiatry/neurology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. He stayed on at Mount Sinai to earn an M.S. degree in community medicine and completed a preventative medicine fellowship, rose to associate professor of psychiatry, of geriatrics, and of community medicine—and reconnected with Dr. Strain, who was there. “Jim ended up becoming a mentor then, and we worked together for almost twenty years in mind/body dualism,” he says. They co-authored dozens of papers at the interface of psychiatry and physical illness, covering congestive heart failure and depression; alcohol use disorder and depression in elderly patients; ways in which psychiatric issues affect hospital stays; and more. They also developed screening devices for depression, alcoholism, and cognitive impairment in the elderly. Among Dr. Fulop’s contributions to clinical practice were the Five D’s of geriatric psychiatry: delirium, dementia, depression, drugs (medications and substance abuse, and adverse effects), and medical disorders mimicking psychiatric conditions. They appeared in the Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology (1998) in the chapter he contributed, “Characterization and Management of Behavioral Disturbances in the Elderly.” His work improved how geriatric patients and patients with mental illness in the hospital are screened, treated, and paid for. Dr. Fulop recounts, with a smile, a recent visit to the doctor in which he took his own screening test!

Learning Physical Examination, AECOM, 1978 (Dr. Fulop and Thomas Coffee, M.D. ’80)

Learning Physical Examination, AECOM, 1978 (Dr. Fulop and Thomas Coffee, M.D. ’80)

Speaking from Experience

After 15 years of practicing his personal blend of geriatric medicine, preventive medicine, and psychiatry, Dr. Fulop’s expertise led him to a medical directorship at Merck & Co., Inc. “Our disease management programs for depression screening, evaluation, and treatment enrolled not one patient or a thousand—it was in the millions,” he says. He continued with a focus on public health in the private sector as a vice president of biotechnology and life sciences equity research at Needham & Company, LLC, where he matched investors with companies that ultimately contributed to the pandemic response.

Dr. Fulop offers sage advice to Einstein medical students. “When you come to a fork in the road, take it—thank you, Yogi Berra,” he says. “If something pushes you away, maybe something is pulling you. Try and identify it.” Find a mentor who makes you think “Hey, I want to do what they’re doing,” he advises. Finally, he says, “Complete your medical training. Otherwise, you’re just another smart person with ideas but you don’t have the experience to leverage to help patients.”

Albert and Irene Fulop, parents, New York, 1959

Albert and Irene Fulop, parents, New York, 1959

The Long View: Gratitude

Dr. Fulop, now an independent biotech analyst in Las Vegas, is sponsoring the George Fulop, M.D. ’80, and Family Endowed Assistant Professorship in neuroscience at Einstein. “Only in America can you come as an immigrant with nothing and return something like a professorship in a lifetime,” he says. Note that the professorship mentions the family who gave him his first opportunities. And it is for an assistant professor, someone early in their career—one of seven newly endowed assistant professorships in basic sciences at Einstein. Says Yaron Tomer, M.D., Einstein’s Marilyn and Stanley M. Katz Dean, “Dr. Fulop’s gift is very much in step with Einstein’s initiative to hire and retain innovative early and mid-career faculty, with the ultimate goal of energizing our basic science departments.” A portion of a 100M anonymous gift that Einstein received in 2023 matches the gift.

Dean Tomer adds that by helping us recruit brilliant early career scientists, this assistant professorship will serve to advance our knowledge in neuroscience and our standing as a preeminent research institution. Dr. Fulop envisions the holder of his assistant professorship doing research on the interface of psychiatric and physical states, an area he has studied for years. He views that interface as the overlapping part of a Venn diagram, with slivers of pure psychiatry and pure medicine off to the sides. “All medical conditions affect the mind, and the mind can affect how medical care is given,” says Dr. Fulop. “Whether one is the prime driver of the other is hard to tease out, so you need to address it holistically, which is the basis of my career. What I’d like to see come out through this professorship is more understanding of that clinical and basic science interface.”

It seems highly likely that a brilliant young neuroscientist will be interested.